When standup comedian Tom Allen obtained Attitude journal’s comedy award final yr, he used his acceptance speech to salute the subversive wits who paved the manner for freedoms now loved by queer individuals in Britain. Joining Oscar Wilde and Noël Coward on the record was an actor and raconteur singled out by Allen as “a big hero of mine”, and feted by everybody from Orson Welles to Judy Garland, Maggie Smith to Morrissey.

“I wanted to mention Kenneth Williams because he was so profound,” Allen tells me. “And yet, because he was also funny, that profundity hasn’t been acknowledged. As a child, I connected with his outsiderness. Rather than trying to fit in, he went in the opposite direction. Not only did he not apologise for being different, but he was queer in every sense, truly at odds with the world in which he found himself.”

Williams, born to working-class London mother and father 100 years in the past, on 22 February 1926, was near ubiquitous in British tradition in the second half of the final century. On stage, display screen and radio, from bawdy comedies to chatshows and youngsters’s leisure, his adenoidal voice was inescapable. Up and down the class scale it slid, swanee whistle-style, from sandpapery cockney to Sandringham pomp, the elasticated vowels so capacious you may run round in them.

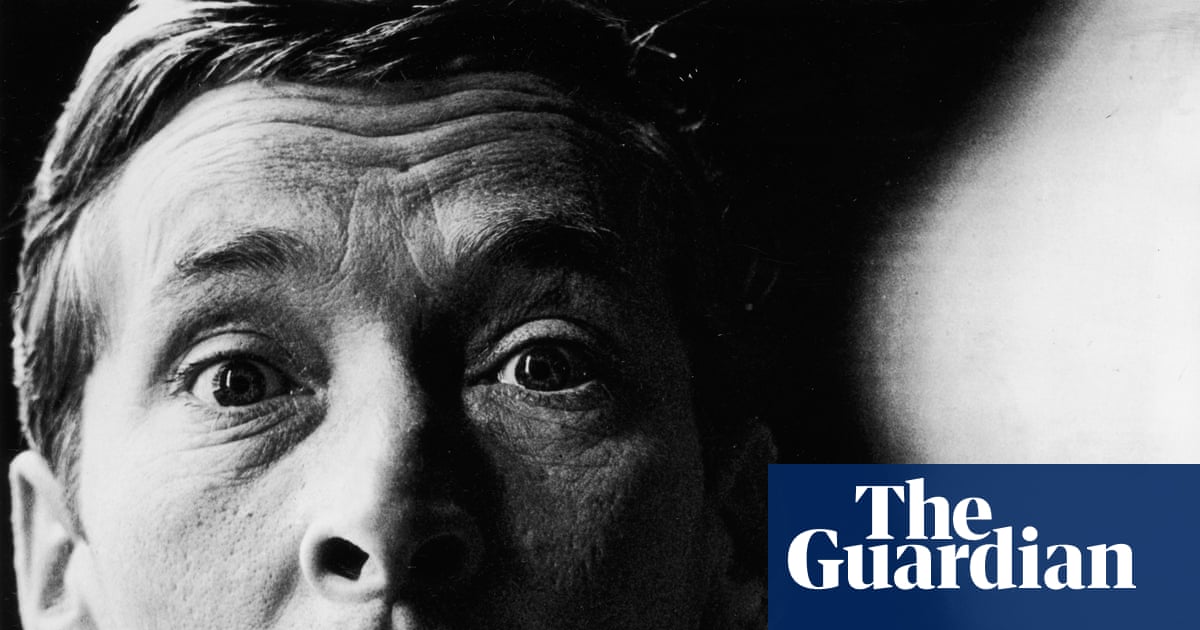

Physically, too, he was distinctive. He described himself as a “dried-up prune-like poof” however the actuality was extra arresting: he was like a residing Gerald Scarfe caricature, the flared nostrils vast as shotgun barrels, the twitching eyebrows telegraphing disdain, prurience or relish, the pinprick eyes glinting at whichever punchline or put-down was coming over the horizon. When he tipped his head again and peered at the viewers down his knife of a nostril, he had the look of an anteater about him. But his species of comedy – erudite and highfalutin one second, vulgar the subsequent – put him in thoughts of an altogether completely different creature. “Perhaps it’s my duty to be a sort of mosquito,” he mentioned. “Someone’s got to continually remind people that we are animal.”

Michael Sheen, who performed him in the 2006 BBC movie Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa!, believes this was a significant half of his attraction. “He would be chatting about something intellectual and high-class, then suddenly be talking about his bumhole,” he says. “That lent him a sort of danger and spontaneity. He’s like a commedia dell’arte character, or the fool or trickster in mythology – he delights in pricking pomposity and turning expectations upside down. It’s about saying: ‘This is what is respectable. But here is the murky stuff underneath.’ There was nobody better at doing that than him. What David Lynch did for America, Kenneth Williams did for Britain, but in the form of light entertainment.”

Williams is finest recognized as we speak as a mainstay of the coarse, innuendo-drenched Carry On films. He whinged, snorted and scoffed his manner by means of 26 of them, together with Carry On Cleo (“Infamy, infamy, they’ve all got it in for me!”) and Carry On Camping, which distilled his curdled, priggish essence into one indelible picture: Barbara Windsor’s bikini prime being catapulted on to his horrified face throughout an overenthusiastic morning exercise.

His remaining contribution to the collection got here in 1978 in the dismal Carry On Emmannuelle [sic], during which he performs the French ambassador, frequently refusing intercourse with his younger spouse (Suzanne Danielle) on account of an harm sustained throughout a unadorned parachuting accident. His co-star – now Suzanne Torrance – remembers him as variety and cheerful. “He was the ultimate professional,” she says. “He treated me so well and never acted like the star.” His nude scenes – he drops his underwear twice inside the movie’s first 10 minutes – had been a selected delight for him. “Oh, he loved showing his bum. Loved it. He joked about his bottom hanging in pleats.”

There was much more to Williams, although, than his Carry On tomfoolery. In 1950, he understudied Richard Burton as Konstantin in a Swansea manufacturing of The Seagull. Orson Welles, who directed Williams on stage in London in Moby Dick, tried to steer him to come back to New York to play the Fool in King Lear. Judy Garland knew his sketches by coronary heart, having “worn out the grooves” of the vinyl recordings of his 1959 theatrical revue, Pieces of Eight (during which his understudy was firebrand-to-be Ken Loach, who later mentioned of him: “He was very nice … but he could be capricious. Sometimes, he just cut you dead”).

Peter Cook, who wrote some of the materials in that present, predicted Williams “could be the funniest comic actor in the world”, whereas the critic Kenneth Tynan saluted his “matchless repertory of squirms, leers, ogles and severe, reproving glares” and anointed him “the petit-maître of contemporary camp”. After Williams’ loss of life in 1988, Morrissey praised “his bomb-shelter Britishness, his touch-me-not wit, his be-ironed figure, stylishly non-sexual” and famous that “his facial features were as funny as anything he ever said”.

Maggie Smith, who grew to become Williams’ shut buddy after starring with him in the 1957 revue Share My Lettuce, referred to as him “an enormous influence” and admitted: “I pinch from him all the time.” Until she labored with him, mentioned Smith, she had “never thought of colouring things as vividly as Kenneth does. I’d never thought that one could make a speech that alive.” More than twenty years after his loss of life, he was nonetheless inspiring her. The biographer Roger Lewis credit the comedian as one of the sources of Smith’s efficiency in Downton Abbey. The desiccated, withering Dowager Countess of Grantham, Lewis wrote, quantities to “Lady Bracknell as played in drag by Williams”.

As a youth and through his nationwide service, Williams labored as an apprentice cartographer. But what put him on the comedy map had been his stints on nationally adored radio reveals similar to Hancock’s Half Hour and, later, Round the Horne. On Hancock’s Half Hour, which drew listeners in the tens of millions, Williams performed a rogues’ gallery of irksome neighbours and popularised a snivelling catchphrase: “Stop messin’ about!” He proved such successful that the present’s star, Tony Hancock, jealously demanded he be written out.

On Round the Horne, Williams and Hugh Paddick performed the camp duo Julian and Sandy, whose banter, written by Marty Feldman and Barry Took, consisted fully of double entendres and the homosexual slang Polari. A prohibition on specific language facilitated some of the filthiest innuendoes ever heard on British radio. Called upon by the avuncular host, Kenneth Horne, to spruce up the environment, Williams exclaimed: “Interior decor? Oh yes, Mr Horne, we’ll shove a couple of creepers up your trellis.”

First broadcast in 1965, two years earlier than the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality between males over 21 in England and Wales, the sketches had been subversive in addition to humorous. “The whole thing was outrageously rude and queer,” says Allen. “In a subtle, mainstream way, he changed attitudes hugely in this country. He was a queer person who people could love through laughter, and that was massive.” Not that Williams’ relationship with his sexuality was simple. Squirming disgrace had at all times been half of his comedy, and he typically recoiled from effeminacy in different males.

Reviewing his autobiography, Just Williams, in 1985, George Melly wrote: “Someone who disliked him intensely couldn’t have done a better hatchet job.” But the extent of Williams’ self-loathing grew to become obvious solely with the posthumous publication, in 1993, of an edited assortment of the diaries he had been preserving since his teenagers. Most of his vitriol was turned on himself, although others got here below hearth, too, whether or not colleagues (particular enmity was reserved for his fellow Carry On common Sid James, in addition to for Hancock) or individuals of color: “[Enoch] Powell was right, they should have stopped immigration years ago,” he wrote in 1979.

Now the world additionally knew the tortured, if barren, state of his intercourse life. “He would always say he was homosexual by nature, not practice,” says David Benson, who first performed him on stage in 1996 in Kenneth Williams: Think No Evil of Us and is now touring My Life With Kenneth Williams. “He was celibate, and this intense internal pressure and conflict was partly what drove his comedy.” Sheen agrees: “The sense of not wanting to be penetrated by anything is central to him,” he says. “I don’t just mean sexually. He created this baroque personality that could so easily collapse if touched. It was to be admired only from the outside. There’s something wonderful about that but also tragic because it required that nobody get too close.”

No one did. Though that doesn’t imply he was a chilly fish. Glyn Grimstead, who was 18 when Williams directed him in a 1981 London revival of Joe Orton’s four-hander, Entertaining Mr Sloane, remembers him as “absolutely delightful. Ken and I would catch the train home together. He’d get off at Great Portland Street and I’d go on to Plaistow. For me, it was a Professor Higgins/Eliza Doolittle relationship. I was very cockney, Ken wasn’t. He would teach me new words, correct my grammar. I loved it. Only later did I realise he came from the Caledonian Road [in London] and was as rough as I was. He was always jolly and lively. You would never have suspected he was desperately unhappy until you read the diaries.”

Turning distress into comedy had at all times been Williams’ speciality. “He would go on chatshows and say, ‘Ooh, I had a terrible night with my bowels. Agony, it was!’” says Benson. “People would fall about laughing but this was real pain he was talking about, as we know from the diaries. It wasn’t a joke, but he made it one, which is admirable.”

Williams had imprecise plans for his dotage. “I pay in a pension fund for when I’m over 60,” he mentioned in 1967. “I’d like a cottage by the sea.” In truth, he died in his spartan London flat in the block the place his beloved mom lived, lower than two miles from the place he was born. He was 62, the similar age at which his father, a gruff hairdresser who scorned his son’s plummy tones and camp method, had died. Williams at all times maintained that his father’s loss of life from consuming poison had been suicide moderately than an accident. An equal ambiguity hung over his personal loss of life from an overdose of barbiturates; the coroner recorded an open verdict. The remaining line in Williams’s diary (“Oh – what’s the bloody point?”) has been extensively interpreted as a suicide observe, although it was additionally a well-known expression of the despair that surfaced repeatedly all through the tens of millions of phrases in these journals.

“He regretted not being taken seriously,” says Allen. “The great tragedy is he did something enormously serious through his comedy, which he could never realise or acknowledge. He wasn’t seen as an activist, and would probably hate to have been. What we sometimes forget, though, is that radical action comes in many forms.”

‘The second night, he wore a deerstalker like Sherlock Holmes’: Ian McShane on working with Williams

In 1965, Williams performed Inspector Truscott in the first manufacturing of his buddy Joe Orton’s black comedy, Loot. After 56 performances, throughout which the solid needed to study three completely different drafts whereas touring, the manufacturing closed in Wimbledon, south London. Williams referred to as it “the most painful period of my life”. The solid included a 22-year-old Ian McShane. His recollections as we speak distinction with Williams’ contemporaneous diary entries.

Ian McShane: Ken was humorous and charming. He and I received on very properly. A pair of occasions we had dinner collectively at his favorite restaurant, The Seven Stars, in Joe Lyons’ Corner House. An Angus steak, a prawn cocktail and a black forest gateau: the top of sophistication. I additionally went again to his “rooms” as he referred to as them, close to Regent’s Park, and we had tea and a chat and labored on our strains. I used to be very fond of him.

Kenneth Williams: Ian McShane got here again … He is v. prepared and tremendously gifted. I like him. This morning I corrected him on a incorrect studying of a line and mentioned, “If you’d read the script properly, you wouldn’t make such a mistake …” and he mentioned he’d been damage by my shouting that at him in rehearsal. I apologised. One frequently forgets how delicate individuals are. (27 January 1965)

IM: Rehearsals had been terrific till a pair of weeks in, once I assume Ken began to get scared. I keep in mind throughout one heated dialogue, I mentioned, “Can’t we just do the play?” and that earned me a withering look from Ken. There had been fixed requires rewrites. That didn’t faze Joe, as a result of he may come out with that dialogue in his sleep.

KW: Script in rags. Cast is completely demoralised. I shouldn’t have set foot close to this rotten mess. (10 February 1965)

IM: The manufacturing was overshadowed by Ken eager to be humorous all the time. If he wasn’t getting amusing, he would resort to sticking his bum out or doing 17 completely different accents. The first night time was weird. We opened in Cambridge and he got here out wearing a black raincoat. It was like, “What the fuck is he doing?” He regarded like the Gestapo! The second night time, he wore a deerstalker like Sherlock Holmes. He was genuinely humorous – he simply received nervous about the materials. It was meant to go to the West End, so it was unhappy to complete in Wimbledon of all locations.

A West End manufacturing in 1966 was successful. Williams directed Loot at the Lyric Hammersmith, London, in 1980.